“GOT TO KEEP ON LOVING”

– Mahou Shoujo Magical Destroyers

In Akihabara circa 2007, a chorus of voices echoed through the electric town: ‘Let me keep my Haruhi!’ A diverse assembly of men and women, young and old, collectively known as the Revolutionary Moé Advocates Alliance, protested down the streets of Akiba. Clad in colorful anime costumes and various popular internet memes from the era, they marched with vigor and passion. Their well-practiced slogans and anisongs resonated through their haven. This was a protest against the transformation unfolding within Akihabara.

The Revolutionary Moé Advocates Alliance wasunited by a shared love for fictional characters. They raised an outcry over what they perceived as Akihabara losing it’s ‘soul’. The rise of big department stores threatened the unique charm of the sacred ground, overshadowing the quaint shops merchandising hobby goods and electronic components. Otaku, feeling a connection to their space of 2D love, banded in protest against what they believed to be the changing face of Akihabara.

In the social climate of the early 2000s, Otaku were treading on the border between acceptable and unacceptable. The otaku namesake was tainted by the four gruesome murders that took place between August 1988 and June 1989 at the hands of Tsutomu Miyazaki, also dubbed the “Otaku Murderer.” Aside from the numerous unfortunate instances leading up to his murders, Tsutomu produced doujin work and attended the comic market during his free time.

Japan is quite proud of the relatively low instances of violent crime within the country. The news media at the time reported that Tsutomu Miyazaki was not just a serial killer; he was also an otaku. This was one of the most important public depictions of otaku and shaped many perceptions of their culture. The news implied that Tsutomu committed the crime because he was not able to distinguish reality from fiction. One look at his Wikipedia article and you’ll know his story, and it isn’t as black and white as it was portrayed. Still, this was the first report on Otaku, and it set them back quite a lot.

Now that it’s 2023 and anime has become mainstream to the point that I could walk outside in my American city for 4 minutes and find a car with Chainsaw Man stickers attached to its bumper…

Why is Magical Destroyers still hung up on this?

otaku should be oppressed, actually

Before we look deeper into Magical Destroyers, it’s important to get an idea of the person who created this potential series. Jun Inagawa is a multimedia artist who tends to lean towards his “unapologetic otaku” style. He works on a lot of projects and collaborations with brands; he even works with artists that I personally follow, like DAOKO and BiSH. His works are quite popular, and you’ve likely seen something he’s drawn before. In fact, I think I’ve seen him IRL at Anime Expo 2023 since he was DJing for King Records on the entertainment floor.

His style regularly incorporates rough and edgy magical girl characters. A big part of that design comes from the idea that magical girls are powerful and perfect ideals. He believes that it would be pretty cool if he drew them doing more “human” things, like, uh, smoking and doing drugs. It’s certainly not my style, but I can’t knock him for it; he’s got a vision, and he’s pretty gung-ho about what he likes.

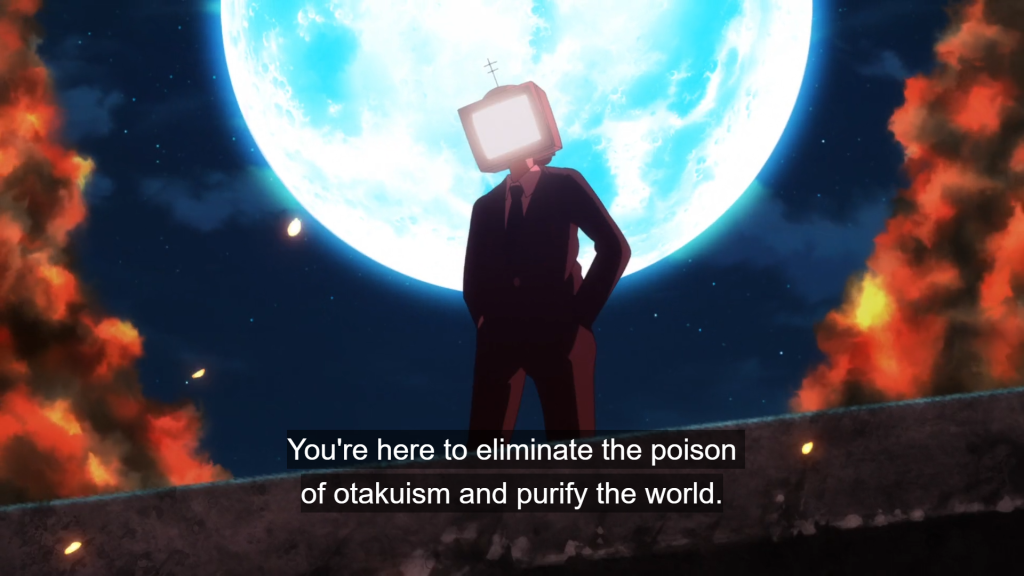

Magical Destroyers is set in a dystopian Japan, where the government decides, for no discernible reason, that otaku need to be “protected” (imprisoned). Years after the SSC invaded Akihabara, the otaku were left in small numbers, taking refuge in a hidden area in Akiba. Otaku Hero, our main character, leads a small group of otaku and his magical girls to fight against the oppression of the SCC.

It may sound interesting to some, but I think the concept is incredibly boring. It’s a story about oppression against otaku; it’s a commentary on a non-issue. The plot itself is absurdly reliant on trying to garner sympathy for Otaku and for the hardships of liking things. It simply doesn’t work, and frankly, I find its attempts more worthy of cringe than anything else.

From the get-go, the show immediately makes very lowbrow nods to Otaku culture. Our MC walks around Akiba with the signature backpack and poster combo. He goes to a shop and finds out that the SCC is taking all of their stuff—their precious otaku goods. Instead of something tasteful like the eroge in Oreimo, this show simply throws vague objects resembling popular otaku merchandise at the viewers. Bodypillows! Figures! Model Kits! Idols! Video Games! Arcade PCBs! That one random scene with the MC celebrating the birthday of his waifu! It casts a net, trying to gain the attention of every possible hobby an Otaku might have. It would be inconsequential if the show wasn’t trying to shove this down your throat every 5 minutes. Honestly, it comes off as “try-hard.”

The message behind Magical Destroyers is that it is fine to do what you like and that being an otaku is OKAY even if society is against it. The anime struggled to convey such a simple message. Despite the entire premise being built directly upon this ideal, it couldn’t stick even when every single character practically screamed in agony, “I LOVE BEING AN OTAKU.” The issue comes from how horribly inconsistent it was in telling its story.

The plot is genuinely nothing—nothing at all. It begins with the appropriate set-up for the story, but problems resolve far too quickly. They need to get the rest of the magical girls to launch a large-scale attack against the SCC, but the kicker here is that they complete this task by episode 2. The rest of the episodes serve as “development” for our characters, if you can even call it that. It’s just the characters in various episodic incidents with the occasional “banked” transformation segment. The show only picks up around episode 8, where something actually happens in the story; even then, the episodes before were completely irrelevant, so much so that I genuinely believe you can watch Episode 1 and skip all the way to episode 8 and be caught up in most of the developments.

Even then, without the “plot” being concerned, the show simply did not know how to handle itself after its pilot episode. The setting was depicted as somewhat of a dark comedy, with tongue-in-cheek references and people being slaughtered because of love. Episode 1 features Otaku Hero’s revolutionary group struggling against the oppressive SSC. Episode 2 has an underground club with Pink parading around with her followers and doing copious amounts of drugs. All of a sudden, on episode 4, it’s a beach episode. Of course, it’s a nod to the stereotypical SoL anime and its incessant need for bikinied teenagers, but it has absolutely no place in this series, at least tonally. You can’t take this show seriously from any point of view. Half of the random gags thrown in just make everything else feel rather pointless.

The social commentary is half baked—no, 1/4 baked. It feels as though the author, equipped with a surface-level understanding of Otaku culture from a wiki page, attempted to craft a philosophical thesis while embodying the culture. An incoherent mess that constitutes absolutely nothing, wearing a cashmere coat of “chaos” and “revolution,” with dreams of becoming something larger than life, something worth your time. It fails to be anything more than another anime in Spring 2023’s catalog, likely to be overlooked and forgotten. Perhaps, in this case, that’s for the best.

Leave a Reply